The history of human settlements in India goes back to prehistoric times. No written records are available for the prehistoric period. However, plenty of archaeological remains are found in different parts of India to reconstruct the history of this period.

They include the stone tools, pottery, artifacts and metal implements used by pre-historic people. The development of archaeology helps much to understand the life and culture of the people who lived in this period.In India, the prehistoric period is divided into the Paleolithic(Old Stone Age), Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age), Neolithic (New Stone Age) and the Metal Age. However, these periods were not uniform throughout the Indian subcontinent. The dating of the prehistoric period is done scientifically. The technique of radio-carbon dating is commonly used for this purpose.

PALEOLITHIC OR OLD STONE AGE

The Old Stone Age sites are widely

found in various parts of the Indian subcontinent. These sites are generally

located near water sources.Several rock shelters and caves used by the Paleolithic

people are scattered across the subcontinent. They also lived rarely in huts

made of leaves. Some of the famous sites

of Old Stone Age in India are:

a. The Soan valley and Potwar

Plateau on the northwest India.

b. The Siwalik Hills on the north

India.

c. Bhimpetka in Madhya Pradesh.

d. Adamgarh hill in Narmada valley.

e. Kurnool in Andhra Pradesh and

f. Attirampakkam near Chennai.

In the Old Stone Age, food was

obtained by hunting animals and gathering edible plants and tubers. Therefore,

these people are called as hunter-gatherers. They used stone tools, hand-sized

and flaked-off large pebbles for hunting animals. Stone implements are made of

a hard rock known as quartzite. Large

pebbles are often found in river terraces. The hunting of large animals would

have required the combined effort of a group of people with large stone axes.We

have little knowledge about their language and communication. Their way of life

became modified with the passage of time since they made attempts to

domesticate animals, make crude pots and grow some plants. A few Old Stone Age

paintings have also been found on rocks at Bhimbetka and other places. The

period before 10000 B.C. is assigned to the Old Stone Age

MESOLITHIC OR MIDDLE STONE AGE

The next stage of human life is

called Mesolithic or Middle Stone Age which falls roughly from 10000 B.C. to

6000 B.C. It was the transitional phase between the Paleolithic Age

and Neolithic Age. Mesolithic remains are found in Langhanj in Gujarat, Adamgarh

in Madhya Pradesh and also in some places of

Rajasthan, Utter Pradesh and Bihar. The paintings and engravings found at the

rock shelters give an idea about the social life and economic activities of

Mesolithic people. In the sites of Mesolithic Age, a different type of stone

tools is found.These are tiny stone artifacts,

often not more than five centimeters in size,and therefore called microliths.

The hunting-gathering pattern of life continued during this period. However,

there seems to have been a shift from big animal hunting to small animal

hunting and fishing. The use of bow and arrow also began during this period.

Also, there began a tendency to settle for longer

periods in an area. Therefore, domestication of animals,horticulture and

primitive cultivation started. Animal bones are found in these sites and

these include dog, deer, boar and ostrich. Occasionally, burials of the dead

along with some microliths and shells seem to have been practiced.

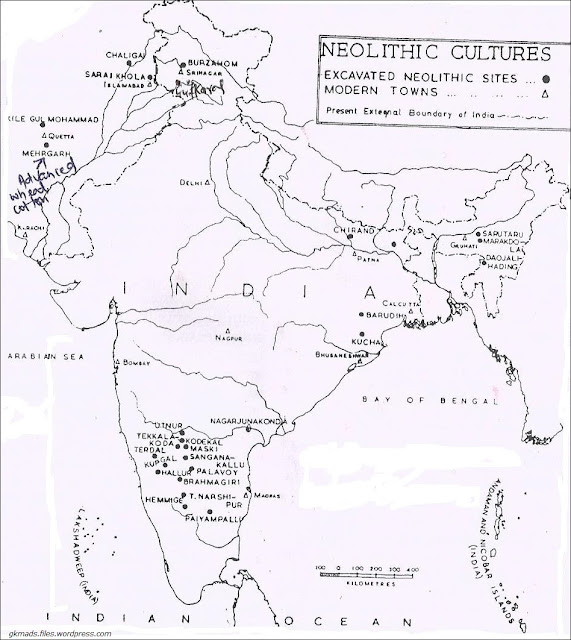

NEOLITHIC AGE

A remarkable progress is A

remarkable progress is noticed in human civilization in the Neolithic Age. It

is approximately dated from 6000 B.C to 4000 B.C. Neolithic remains are found in

various parts of India. These include the Kashmir valley, Chirand in Bihar,

Belan valley in Uttar Pradesh and in several places of the Deccan. The

important Neolithic sites excavated in south India are Maski, Brahmagiri, Hallur

and Kodekal in Karnataka,Paiyampalli in Tamil Nadu and Utnur in Andhra

Pradesh.The chief characteristic features of the Neolithic culture are the practice

of agriculture,domestication of animals, polishing of stone tools and the

manufacture of pottery. In fact, the cultivation of plants and domestication of

animals led to the emergence of village communities based on sedentary life.

There was a great improvement in technology of making tools and other equipment used by man. Stone tools were now polished. The polished axes were

found to be more effective tools for hunting and cutting trees. Mud brick houses

were built instead of grass huts. Wheels were used to make pottery. Pottery was

used for cooking as well as storage of food grains. Large urns were used as coffins for the burial of

the dead. There was also improvement in agriculture. Wheat, barely, rice,

millet were cultivated in different areas at different points of time. Rice

cultivation was extensive in eastern India. Domestication of

sheep, goats and cattle was widely prevalent. Cattle were used for cultivation

and for transport. The people of Neolithic Age used clothes made of cotton and

wool.

METAL AGE IN INDIA

The Neolithic period is followed by

Chalcolithic (copper-stone) period when copper and bronze came to be used. The

new technology of smelting metal ore and crafting metal artifacts is an

important development in human civilization. But the use of stone tools was not given up. Some of the micro-lithic

tools continued to be essential items. People began to travel for a long

distance to obtain metal ores. This led to a network of Chalcolithic cultures and

the Chalcolithic cultures were found in many parts of India.Generally,

Chalcolithic cultures had grown in river valleys. Most importantly, the

Harappan culture is considered as a part of Chalcolithic culture. In South

India the river valleys of the Godavari, Krishna,Tungabhadra, Pennar and Kaveri

were settled by farming communities during this period. Although they were not

using metals in the beginning of the Metal Age, there is evidence of copper and

bronze artifacts by the end of second millennium B.C. Several bronze and copper

objects, beads, terracotta figurines and pottery were found at Paiyampalli in

Tamil Nadu.The Chalcolithic age is followed by Iron Age. Iron is frequently

referred to in the Vedas. The Iron Age of the southern peninsula is often

related to Megalithic Burials. Megalith means Large Stone. The burial pits were

covered with these stones. Such graves are extensively found in South India.

Some of the important megalithic sites are Hallur and Maski in Karnataka,

Nagarjunakonda in Andhra Pradesh and Adichchanallur in Tamil Nadu. Black and red

pottery, iron artifacts such as hoes and sickles and small weapons were found

in the burial pits.

BRONZE AGE

Indus civilization

The Indus Valley Civilization was a

Bronze Age civilization (3300–1300 BCE; mature period 2600–1900 BCE, pre-Harappan

cultures starting c.7500 BCE extending from what today is primarily Pakistan,

but also some regions in northwest India and

northeast Afghanistan. Along with Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, it was one of

three early civilizations of the Old World, and the most widespread among them,

covering an area of 1.25 million km2. It flourished in the basins of the Indus

River, one of the major rivers of Asia, and the now dried up Sarasvati River,

which once coursed through northwest India and eastern Pakistan together with

its tributaries flowed along a channel, presently identified as that of the

Ghaggar-Hakra River on the basis of various scientific studies. Indus Valley Civilization

along with Mesopotamia and Egypt is regarded as cradle of civilization. At its

peak, the Indus Civilization may have had a population of over five million. Inhabitants

of the ancient Indus river valley developed new techniques in

handicraft(carnelian products, seal carving) and metallurgy (copper, bronze,

lead, and tin). The Indus cities are noted for their urban planning, baked

brick houses, elaborate drainage systems,water supply systems, and clusters of

large non-residential buildings.The Indus Valley Civilization is also known as

the Harappan Civilization, after Harappa, the first of its sites to be

excavated in the 1920s, in what was then the Punjab province of British India, and is now in Pakistan. The

discovery of Harappa, and soon afterwards, Mohenjo-Daro, was the culmination of

work beginning in 1861 with the founding of the Archaeological Survey of India

in the British Raj. Excavation of Harappan sites has been ongoing since 1920,

with important breakthroughs occurring as recently as 1999.There were earlier and later cultures, often

called Early Harappan and Late Harappan, and pre-Harappan cultures, in the same

area of the Harappan Civilization. The Harappan civilisation is sometimes

called the Mature Harappan culture to distinguish it from these cultures.

Bhirrana may be the oldest pre-Harappan site, dating back to 7570-6200 BCE. By

1999, over 1,056 cities and settlements had been found, of which 96 have been excavated, mainly in the general

region of the Indus and the Sarasvati River and their tributaries. Among the

settlements were the major urban centers of Harappa, Mohenjo-daro (UNESCO World

Heritage Site), Dholavira, Ganeriwalain Cholistan and Rakhigarhi,Rakhigarhi

being the largest Indus Valley Civilization site with 350-hectare (3.5 km2)

area.The Harappan language is not

directly attested and its affiliation is uncertain since the Indus script is

still undecipherable.

MAJOR SITES

The earliest excavations in the

Indus valley were done at Harappa in the West Punjab and Mohenjodaro in Sind.

Both places are now in Pakistan. The findings in these two cities brought to

light a civilization. It was first called the ‘The Indus Valley Civilization’.

But this civilization was later named as the ‘Indus Civilization’ due to the

discovery of more and more

sites far away from the Indus

valley. Also, it has come to be called the ‘Harappan Civilization’after the

name of its first discovered site. Among the many other sites excavated,the

most important are Kot Diji in Sind, Kalibangan in Rajasthan, Rupar in the

Punjab, Banawali in Haryana, Lothal, Surkotada and Dholavira, all the three in

Gujarat. The larger cities are approximately a hundred

hectares in size. Mohenjodara is the largest of all the Indus cities and it is

estimated to have spread over an area of 200 hectares.There are four important

stages or phases of evolution and they are named as pre

Harappan,early-Harappan, mature-Harappan and late Harappan. The

pre-Harappan stage is located in eastern Baluchistan. The excavations

at Mehrgarh 150 miles to the northwest of Mohenjodaro reveal the existence of

pre-Harappan culture. In this stage, the nomadic people began to lead a settled

agricultural life. In the early-Harappan stage, the people lived in large

villages in the plains.

There was a gradual growth of towns in the Indus valley. Also, the transition

from rural to urban life took place during this period. The sites of Amri and

Kot Diji remain the evidence for early-Harappan stage. In the mature-Harappan

stage, great cities emerged. The excavations at Kalibangan with its elaborate

town planning and urban features prove this phase of evolution. In the

late-Harappan stage, the decline of the Indus culture started. The excavations

at Lothal reveal this stage of evolution. Lothal with its port was founded much

later. It was surrounded by a massive brick wall as flood protection. Lothal

remained an emporium of trade between the Harappan civilization and the

remaining part of India as well as Mesopotamia.

FEATURES

OF URBANIZATION

A sophisticated and technologically

advanced urban culture is evident in the Indus Valley Civilization making them

the first urban centers in the region. The quality of municipal town planning

suggests the knowledge of urban planning and efficient municipal governments which

placed a high priority on hygiene, or, alternatively, accessibility to the

means of religious ritual.

Town

Planning

The Harappan culture was

distinguished by its system of town planning on the lines of the grid system–that

is streets and lanes cutting across one another almost at right angles thus dividing

the city into several rectangular blocks. Harappa, Mohenjodaro and Kalibangan

each had its own citadel built on a high podium of mud brick. Below the citadel

in each city lay a lower town containing brick houses, which were inhabited by

the common people. The large-scale use of burnt bricks in almost all kinds of

constructions and the absence of stone buildings are the important characteristics

of the Harappan culture. Another remarkable feature was the underground

drainage system connecting all houses to the street drains which were covered

by stone slabs or bricks.

Great

Bath at Mohenjodaro

The most important public place of

Mohenjodaro is the Great Bath measuring 39 feet length, 23 feet breadth and 8

feet depth.Flights of steps at either end lead to the surface. There are side rooms

for changing clothes. The floor of the Bath was made of burnt bricks. Water was drawn from a large well in an

adjacent room, and an outlet from one corner of the Bath led to a drain. It must

have served as a ritual bathing site.

Granary

Sanitation

systems

As seen in Harappa, Mohenjo-Daro and

the recently partially excavated Rakhigarhi, this urban plan included the world's

first known urban sanitation systems, hydraulic engineering of the Indus Valley

Civilization. Within the city, individual homes or groups of homes obtained water from wells. From a

room that appears to have been set aside for bathing, waste water was directed

to covered drains, which lined the major streets. Houses opened only to inner

courtyards and smaller lanes. The house-building in some villages in the region

still resembles in some respects the

house-building of the Harappans.The ancient Indus systems of

sewerage and drainage that were developed and used in cities throughout the

Indus region were far more advanced than any found in contemporary urban sites

in the Middle East and even more efficient than those in many areas of Pakistan

and India today.

Architecture

The advanced architecture of the

Harappans is shown by their impressive dockyards, granaries, warehouses, brick

platforms, and protective walls. The massive walls of Indus cities most likely

protected the Harappans from floods and may have dissuaded military conflicts.

Although some houses were larger than others, Indus Civilization cities were remarkable

for their apparent, if relative, egalitarianism. All the houses had access to

water and drainage facilities. This gives the impression of a society with

relatively low wealth concentration, though clear social leveling is seen in

personal adornments.

Citadel

The purpose of the citadel remains

debated. In sharp contrast to this civilization's contemporaries, Mesopotamia

and Ancient Egypt, no large monumental structures were built.There is no

conclusive evidence of palaces or temples—or of kings, armies, or priests. Some structures are thought to have been

granaries. Found at one city is an enormous well-built bath (the "Great

Bath"), which may have been a public bath. Although the citadels were walled,

it is far from clear that these structures were defensive. They may have been

built to divert flood waters.

Trade

Most city dwellers appear to have

been traders or artisans, who lived with others pursuing the same occupation in

well-defined neighborhoods. Materials from distant regions were used in the

cities for constructing seals, beads and other objects. Among the artifacts

discovered were beautiful glazed faience beads. Steatite seals have images of

animals, people (perhaps gods),and other types of inscriptions, including the yet un-deciphered writing

system of the Indus Valley Civilization. Some of the

seals were used to stamp clay on trade goods and most probably had other uses

as well.

Authority

and governance

Archaeological records provide no

immediate answers for a center of power or for depictions of people in power in

Harappan society. But, there are indications of complex decisions being taken

and implemented. For instance, the extraordinary uniformity of Harappan

artifacts as evident in pottery, seals,weights

and bricks. These are the major theories:

•There was a single state, given the

similarity in artifacts, the evidence for planned settlements, the standardized

ratio of brick size, and the establishment of settlements near sources of raw

material.

•There was no single ruler but

several: Mohenjo-daro had a separate ruler, Harappa another, and so forth.

•Harappan society had no rulers, and

everybody enjoyed equal status

Social

Life

Much evidence is available to

understand the social life of the Harappans. The dress of both men and women

consisted of two pieces of cloth, one upper garment and the other lower garment.

Beads were worn by men and women. Jewelleries such as bangles, bracelets,

fillets,girdles, anklets, ear-rings and fingerings were worn by women. These

ornaments were made of gold, silver, copper, bronze and

semi precious stones. The use of cosmetics was common.Various household

articles made of pottery, stone, shells, ivory and metal have been found at Mohenjodaro. Spindles, needles, combs,

fishhooks, knives are made of copper. Children’s toys include little clay

carts. Marbles, balls and dice were used for games. Fishing was a regular

occupation while hunting and bull fighting were other pastimes. There were

numerous specimens of weapons of war such as axes, spearheads, daggers, bows,

arrows made of copper and bronze.Arts The Harappan sculpture revealed a high

degree of workmanship.Figures of men and women, animals and birds made of

terracotta and the carvings on the seals show the degree of proficiency

attained by the sculptor. The figure of a dancing girl from Mohenjodaro made of

bronze is remarkable for its workmanship. Its right hand rests on the hip,

while the left arm, covered with bangles, hangs loosely in a relaxed posture.

Two stone statues from Harappa, one representing the back view of a man and the

other of a dancer are also specimens of their sculpture. The pottery from

Harappa is another specimen of the fine arts of the Indus people. The pots and

jars were painted with various designs and colors. Painted pottery is of

better quality. The pictorial motifs consisted of geometrical patterns like

horizontal lines, circles, leaves, plants and

trees. On some pottery pieces we find figures of fish or peacock.

Script

The Harappan script has still to be

fully deciphered. The number of signs is between 400 and 600 of which 40 or 60

are basic and the rest are their variants. The script was mostly written from right to left. In a few long

seals the boustrophedon method–writing in the reverse direction in

alternative lines–was adopted. Parpola and his Scandinavian colleagues came to the

conclusion that the language of the Harappans was Dravidian. A group of Soviet

scholars accepts this view. Other scholars provide different view connecting

the Harappan script with that of Brahmi. The mystery of the Harappan script

still exists and there is no doubt that the decipherment of Harappan script

will throw much light on this culture.

Religion

From the seals, terracotta figurines

and copper tablets we get an idea on the religious life of the Harappans. The

chief male deity was Pasupati, (proto-Siva) represented in seals as sitting in

a yogic posture with three faces and two horns. He is surrounded by four

animals (elephant,tiger, rhino, and buffalo each facing a different direction).

Two deer appear on his feet. The chief female deity was the Mother Goddess

represented in terracotta figurines. In latter times, Linga worship was

prevalent. Trees and animals were also worshipped by the Harappans. They

believed in ghosts and evil forces and used amulets as protection against them.

Burial

Methods

The cemeteries discovered around the

cities like Mohenjodaro, Harappa, Kalibangan, Lothal and Rupar throw light on

the burial practices of the Harappans.Complete burial and post-cremation burial

were popular at Mohenjodaro. At Lothal the burial pit was lined with burnt bricks

indicating the use of coffins. Wooden coffins were also found at Harappa. The

practice of pot burials is found at Lothal sometimes with pairs of skeletons.

However, there is no clear evidence for the practice of Sati..

DECLINE

There is no unanimous view

pertaining to the cause for the decline of the Harappan culture.Various

theories have been postulated. Natural calamities like recurring floods, drying

up of rivers, decreasing fertility of the soil due to excessive exploitation

and occasional earthquakes might have caused the decline of the

Harappan cities. According to some scholars the final blow was delivered by the

invasion of Aryans. The destruction of forts is mentioned in the Rig Veda.

Also, the discovery of human skeletons huddled together at Mohenjodaro

indicates that the city was invaded by foreigners. The Aryans had superior

weapons as well as swift horses which might have enabled them to become masters

of this region.A possible natural reason for the Indus Valley Civilization’s

decline is connected with climate change that is also signaled for the neighboring areas of the Middle East: The Indus valley climate grew

significantly cooler and drier from about 1800 BCE, linked to a general weakening of the monsoon at that

time. Alternatively, a crucial factor may have been the disappearance of

substantial portions of the Ghaggar Hakra river system. A tectonic event may

have diverted the system's sources toward the Ganges Plain, though there is

complete uncertainty about the date of this event, as most settlements inside

Ghaggar-Hakra river beds have not yet been dated. The actual reason for decline

might be any combination of these factors. A 2004 paper indicated that the

isotopes of sediments carried by the Ghaggar-Hakra system over the last 20

thousand years do not come from the glaciated Higher Himalaya but have a Sub-Himalayan source. They speculated

that the river system was rain-fed instead and thus contradicted the idea of a

Harappan-time mighty "Sarasvati" river.Recent geological research by

a group led by Peter Clift investigated how the

courses of rivers have changed in this region since 8000 years ago, to

test whether climate or river reorganizations are responsible for the decline

of the Harappan. Using U-Pb dating of zircon sand grains they found that

sediments typical of the Beas, Sutlej and Yamuna rivers (Himalayan tributaries

of the Indus) are actually present in former Ghaggar-Hakra channels. However,

sediment contributions from these glacial-fed rivers stopped at least by 10,000

years ago, well before the development of the Indus civilization.A research team led by the geologist

Liviu Giosan of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

also concluded that climate change in form of the eastward migration of the monsoons

led to the decline of the Indus Valley Civilization. The team's findings were published in PNAS in May 2012. According

to their theory, the slow eastward migration of the monsoons across Asia

initially allowed the civilization to develop. The monsoon-supported farming

led to large agricultural surpluses, which in turn supported the development of

cities. The Indus Valley residents did not develop irrigation capabilities,relying

mainly on the seasonal monsoons. As the monsoons kept shifting eastward, the

water supply for the agricultural activities dried up. The residents then migrated

towards the Ganges basin in the east, where they established smaller villages

and isolated farms. The small surplus produced in these small communities did

not allow development of trade, and the cities died out

No comments:

Post a Comment